Moral consequentialism is one of many terms that has a double meaning. Looking it up typically yields fairly reasonable-sounding ideas such as judging the morality of an action based on its results, i.e. utilitarianism. However, there is another meaning to moral consequentialism that you should be aware of, and that is the idea that truth is dependent on morality. If an idea has implications that the moral consequentialist finds reprehensible, then that idea must be suppressed, even if it is demonstrably true. If an idea has implications that the moral consequentialist likes, then that idea must be promoted, even if it is demonstrably false. For this reason, moral consequentialism is a logical fallacy. Most people reading this may be tempted to stop there and just use that to shut down any moral consequentialist, but since moral consequentialists do not care if their ideas are logically sound, consider an alternative criticism: moral consequentialism is evil. If truth is subordinated to morality, then morality must be based on something other than reality, and therefore the resulting moral principles will be completely arbitrary. Luckily, there is already a fairly well-developed realist refutation of moral consequentialism.

A particular action is moral or right if it somehow promotes happiness, well-being, or health, or it somehow minimizes unnecessary harm or suffering, or it does both. A particular action is immoral or wrong if it somehow diminishes overall happiness, well-being, or health, or it somehow causes unnecessary harm or suffering, or again it does both. – Scott Clifton

But Sasha, that’s exactly what moral consequentialism is!

No. Moral consequentialists don’t give a rodent’s posterior about happiness, which is precisely why their utilitarian arguments, if they even have any, always devolve into “the ends justify the means” kind of reasoning. What Clifton described is actually the foundation of universal ethics, which is the standard of proper objective morality, also called post-conventional morality. I know it sounds like a consequentialist argument, but it isn’t; moral consequentialists don’t care about actual results as much as intended results, which is why they insist on doing things that demonstrably do not work. “[Insert terrible idea here] has never been achieved, but it remains a noble goal, so we need to keep trying” is the single most common moral consequentialist argument. Consequentialists only fall back on actual results when constructing a motte-and-bailey argument. Their entire philosophy has a massive blind spot, and here is where we finally get into the real substance of my case.

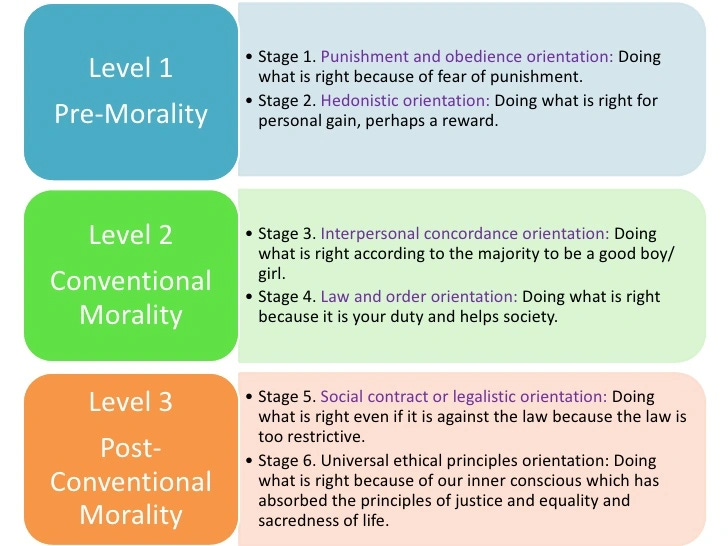

Contrary to popular belief, there are three types of morality, not two. Critics of classical religions have this nasty habit of saying that religious morality is “objective,” and therefore, because what is moral is mostly contextual, then morality is subjective. What they seem to be forgetting is that religious morality is not objective, but absolute. Within a religious doctrine, certain actions are either mandated or proscribed, and while context may be taken into account within the scripture, the overall doctrine leaves little if any wiggle room. Objective morality is more flexible than absolute morality, and subjective morality may as well be non-morality, which is why it is far better to classify systems of morality as pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional. Here’s a chart illustrating how they actually stack up against each other:

Rather than the three types of morality corresponding perfectly to these three levels, subjective morality corresponds to stages 1 through 3, absolute morality corresponds to stage 4, maybe stage 5 depending on the exact nature of the doctrine, and objective morality is stage 6. Political dissidents, especially anarchists, adhere to either stage 2 or stage 6, and their critics – the apparatchiks – typically point to the stage 2 dissidents and use them as an example to strawman the beliefs of the stage 6 dissidents (“libertarians just want freedom from consequences” or the even more hilarious “anarchists are just aspiring dictators”), and that’s because they adhere to stage 3 and 4 morality exclusively, forever straddling the fence between the subjective that will gain prestige within the Cathedral and the absolute which governs their thought through the proverbial carrot-and-stick combination of pride and shame. Just as a basic form of mathematics can be expressed in terms of an advanced form (e.g. geometry in terms of calculus), a lower stage of morality can be understood and critiqued in terms of a higher one, but not the other way round. Adherents of conventional morality are capable of dissecting arguments made from a standpoint of pre-morality, but not post-conventional morality, though that hasn’t stopped them from trying.

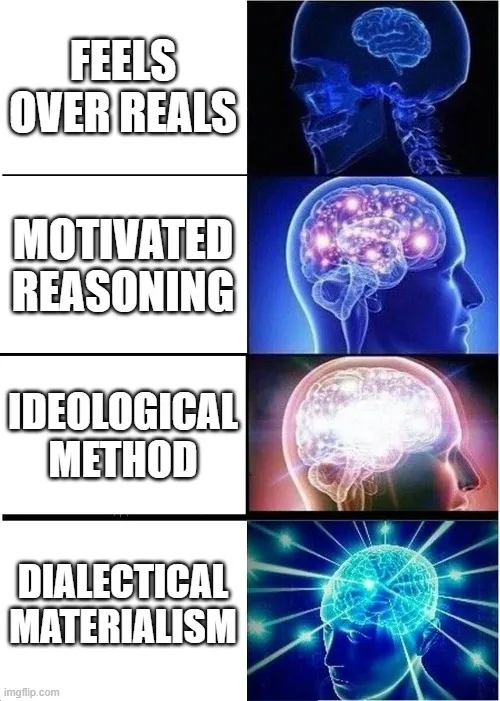

Enter the fake dissident, the longhouse simp, the person who agrees with the establishment and thinks they are part of the resistance. This person is mentally incapable of understanding objective morality, but has probably read works by people who can (a case of what one of my former co-workers called “educated beyond one’s intelligence”), and thinks that they are somehow equipped to critique the political system from a moralistic standpoint as opposed to a purely legal or economic one. What they end up doing instead is resorting to subjective morality and choosing a system of absolute morality dictated by another because they think it will give them the results they want; in other words, they suffer the exact same mental pitfalls as the establishment’s own apologists. In a great deal of cases, they end up engaging in a dialectical synthesis by picking and choosing ideas from different systems, with little to no consideration for whether or not said ideas are even compatible; their attempts to be objective (or, for the particularly radical ones, deny objectivity itself) are driven entirely by emotion masquerading as reason. Whatever term you want to use for this thought process is up to you:

In no case does a person who thinks this way end up creating something coherent, much less internally consistent. One such example is the idea that a nation should have both universal welfare and open borders. Their reasoning is that both of these things are good, therefore both should be implemented, and the realist, who points out that you cannot have both of these things at the same time and also have a functioning economy (which you need for a prosperous society), is a bad person. Realism is bad, but good things are real, apparently.

I don’t know who needs to hear this, but “good” and “real” are not synonyms by any means. The former is a moral judgement, whereas the latter is morally neutral. However, while the philosophy of scientific realism subordinates morality to reality (because we live in the real world, not a moral world), the diametrically opposing philosophy of dialectical materialism turns that idea upside-down. According to dialectical materialism, the real – I’m sorry, the material – world is a reflection of a conscious mind, and therefore, the morality of the real material world is predicated on the morality of the being that manifested the world. According to the classical Hermetics, materialism comes from the mind of the true god, and the real material world is a good thing, albeit imperfect (perfection is found in the “world of forms,” an idea which pre-dates Hermeticism by a few centuries). According to the Gnostics, materialism comes from the mind a false god called the demiurge, and the real material world is an evil illusion. Just as Satanism (by which I mean actual devil worship, not to be confused with LaVeyan Satanism or classical Luciferianism) is a dark mirror image of Christianity, Gnosticism is a dark mirror image of Hermeticism.1

But Sasha, what do occult religions have to do with systems of morality?!

A lot more than you think. Most of the moralistic ideologues out there are philosophically illiterate, and therefore are unaware of the religious origins of their beliefs. Atheists who reject scientific realism on moral grounds have joined a religion without a god, or more precisely, the religion’s real god is deliberately hidden from them and known only to the priests who have disguised themselves as secular academics.2 A lack of belief in gods is not, contrary to what the typical fedora-tipping wannabe edgelord might believe, an indicator of superior intelligence; that would be the recognition that humans aren’t purely rational beings. Bereft of a guiding philosophy for their lives, these completely unguided people turn to pseudo-intellectualism, or the practise of performative intellectual discussion, apparenly hoping to manifest the truth out of rhetoric and sophistry. They spout ideobabble in an attempt to make themselves appear smarter than they actually are, and morality, a topic which they appear to have no understanding of, is one that comes up a lot, especially in the anti-theist circles, because morality is one of the last refuges of classical religion as it is displaced by other ways of thinking.

Hypothetically speaking, how do you think you would react if you met someone who described himself as “a militant atheist,” or “strict materialist” who believed that “nature is the source of all goodness,” was a vegan and a Marxist because of that, and insinuated that you are a creationist for pointing out that some organisms evolved to survive by doing some pretty disgusting things? If your answer is anything other than “I would be completely confused,” then you either think the same way as this person, or you have extensive experience interacting with these nutjobs. By the way, I wasn’t being entirely truthful when I used the word “hypothetically,” because I didn’t make this up, I actually encountered a person who said all these things, he’s the sock puppet of an old enemy of mine, but I’m not sure if what he said was a brief glimpse into my enemy’s true beliefs, or simply a remarkably well-made caricature of a dialectical materialist. I’m leaning toward the former, simply because of the dialectical thought pattern expressed by his public persona as a justification for deceptively re-writing history.3 Anyway, getting back on topic, to the scientific realist, morality is the product of consciousness, therefore all unconscious entities (such as nature itself) are morally neutral. The only exceptions are ideas, because while ideas themselves are not conscious actors, ideas can have morality built in. One such example is a particularly malevolent form of dialectical materialism which holds that, because reality comes from the mind, rather than the other way round, then humans are bad because the social construct4 called human society is the product of selfish minds, and because humanity exists in opposition to nature, nature is good. This should, intuitively, seem like a backwards way of thinking, because it is; empathy, a concept that all social animals have to some extent, flows outward from the individual, diminishing as it gets more distant. It’s the old dinosaur-brained5 way of thinking, “like me good, not like me bad,” that such people have inverted in the misguided belief that they are somehow not subject to the same rules as everything else, because “we are dialectics, we are higher than that.”

In my article on philosophy and political theory, I mentioned that scientific realism is an incomplete philosophy, in that it concerns itself only with the real world, and is not equipped to deal with anything metaphysical. The only thing that scientific realism has to say on the subject is that the mind is the product of the brain. From the mind, any abstract concepts, such as morality, all flow from the brain and its needs, which follow from bodily imperatives. This is why, contrary to what a lot of atheists like to say, it is possible to be a scientific realist and also have a concept of spirituality. In fact, you may have noticed that I like to regularly point out that the greatest scientists throughout history have all studied religion to some extent. For example, Sir Isaac Newton, the father of mechanics and one of the inventors of calculus, was not only a devout Christian, but also an alchemist. If scientific realism had anything to say about spiritual matters, it would be that the spirit world is a reflection of the real world, rather than the other way round. In other words, if there is a spirit world, it would function the same way as the immaterium in Warhammer 40,000. Granted, when you get into the weirder aspects of Big Bang cosmology, that ties in with the Ancient Greek belief that Gaia sprang forth from the Great Void known as Chaos, and I’ve heard conjecture that the cosmic expansion is actually an “unfolding” of a four-dimensional object into three-dimensional space, so for all we know, the dichotomy of real world and spirit world could be some kind of feedback loop. Again, this is pure conjecture, there is nothing remotely scientific about it, which is why other philosophies are necessary to explore such concepts.

Dialectical materialism, on the other hand, is a complete, or more precisely, totalising philosophy, in that it concerns itself with the totality of existence, and so its adherents think that they can have all the answers if only they think hard enough, external input not required. “There is no question you can ask to which you don’t already have the answer,” one of them once told me. No scientist thinks this way. While the scientific realist says that the world we live in came about spontaneously and our consciousness is a product of natural processes, the dialectical materialist says that consciousness existed first, and manifested the material world from a disembodied mind. Whose mind depends on whom you ask. All forms of creationism are borne out of dialectical materialism (both of those terms are relatively new; just because a term for a phenomenon is new doesn’t mean the phenomenon itself is new), so the Christian says “God created the world,” the Hindu says “our world is a dream of Brahma,” and so on and so forth. The atheistic dialectical materialist, unlike the religious disciple or the scientific realist, has no answer to this question. The atheistic dialectical materialist is a creationist who does not believe in any god. Just…

Naturally, this means that the atheist who implies that people who believe in Darwinian evolution are somehow creationists is confessing through projection, thus outing himself as a dialectical materialist, even if he doesn’t know what that means. This is relevant to systems of morality because all dialectical materialists, including the atheistic ones, rely on the same type of morality. Their morality demands a moral law-giver, and where the religious man says “moral laws are divine commands, the gods are the moral law-givers” the atheistic dialectical materialist again has no answer, and thus relies entirely on their own feelings to seek out a moral code that someone else has written. Even in the hypothetical instance that they have the intellectual capability to understand stage 6 morality, their philosophy prohibits them from ever advancing beyond stage 5, possibly even stage 4 depending on their specific doctrine. It is no coincidence that every single dialectical philosopher has promoted some form of social contract theory (which occupies stage 5 along with utilitarianism) at some point, but I’m not talking about them; they are on an entirely different level from the average dialectical materialist.

With all that out of the way, it should be clear why the over-arching principles that dialectical materialists pretend are their own version of universal morality aren’t actually objective, but instead completely arbitrary. Morality that is based in reality denial can never be anything better than a lower stage masquerading as stage 6. Utilitarian arguments, for example, are the basis of the idea that “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.” Ethics that lead to different rules for different people on the basis of “needs” are, by definition, not universal. An example of a universal ethical rule, on the other hand, would be something like the non-aggression principle (NAP), which is widely detested by both secular ideologues and adherents of classical religion. Mind you, the NAP on its own is insufficient to form the basis of universal ethics, which is why people who support it tend to also promote something called physical removal, which is widely misunderstood. I will let MentisWave elaborate (I’ve been citing his videos a lot lately, haven’t I?):

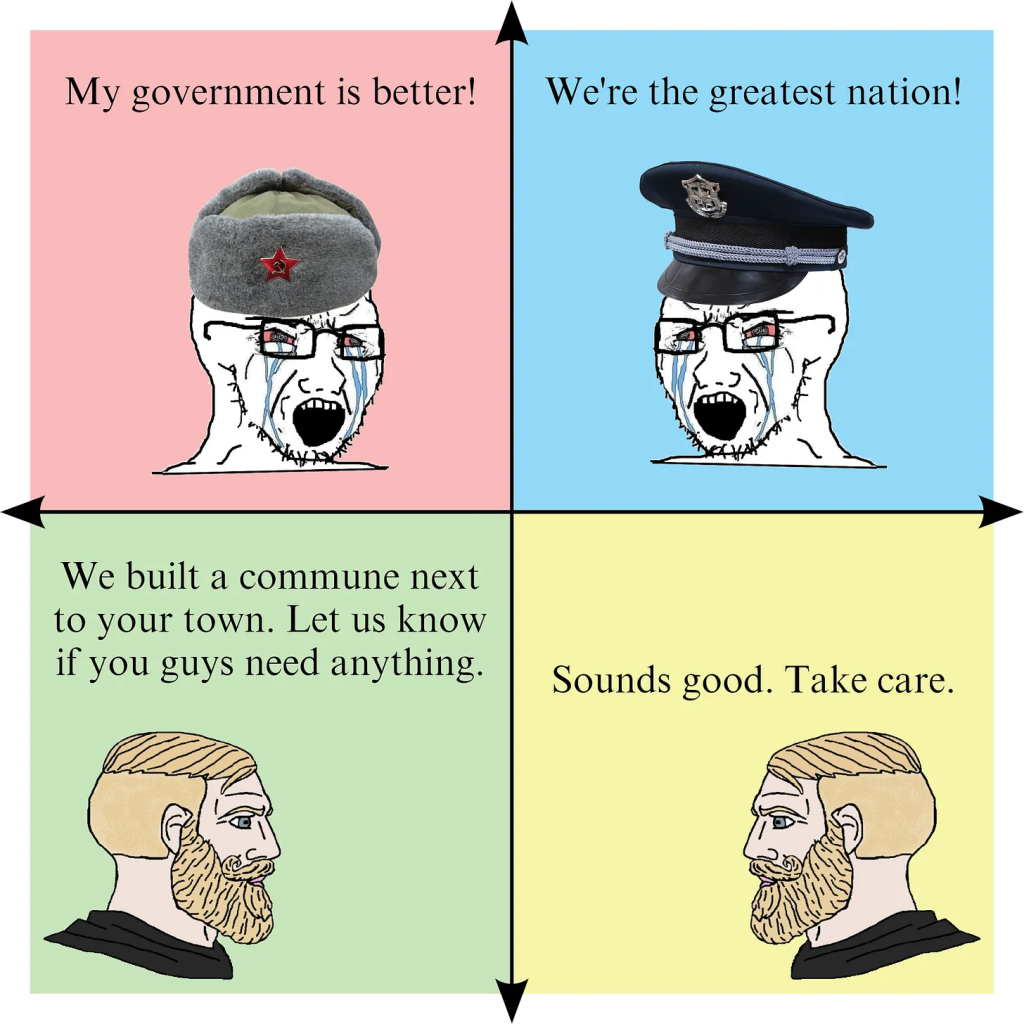

Here’s the deal: since we live in the real world occupied by different people who have inherently incompatible beliefs, people need to be free to dissociate from those who do not share their values, because without that freedom, cultural clashes will occur. Mentis’s favourite example, one which he’s been using for years, is that Muslims need to be free to dissociate from feminists and vice-versa. Using the exact same line of reasoning, I would make the case that people who believe in universal ethics must be free to dissociate from people who subscribe to social contract theory. However, two groups of people who both subscribe to universal ethics but disagree on specific details can coexist in relatively close proximity. While I have more issues than Reader’s Digest with the classic political compass, this meme best illustrates what I mean:

I will elaborate in the future… eventually. There is a certain pathology associated with weird beliefs, and trying to follow the lines of thinking is absolutely dizzying, as round and round you will spin should you get caught in the wheel of the rationalisation hamster. I need to get off this ride now, blow my lunch, have a drink, and write about something easier for a while.

Notes:

1 – I’m going to get crucified if I don’t point out that not all adherents of these religions think this way; Hermeticism, Gnosticism, and Christianity have all been around long enough that they have transformed, split, and re-combined into a dizzying number of sects which all hold vastly different beliefs. Gnostics, for example, don’t even agree on the name of the demiurge: Saklas, Yaldabaoth, and even Yahweh have been used. Classical Luciferians, meanwhile, like to point out that Lucifer and Satan are two different beings, but neo-Luciferians are an entirely different kettle of fish.

2 – Ever since Karl Marx “demystified the dialectic,” dialectical materialists have been worshipping the dialectic itself, rather than the god above and behind the demiurge; their new god is The Idea, rather than a conscious entity like the gods of classical religions. Dialectical materialism would be further secularised a hundred years later, see note 4.

3 – The person in question is a retired history professor who advocates for, among other things, teaching both the 1619 Project and the 1776 Report “in order to reconcile the culture war,” which I likened to teaching that the Earth is both flat and egg-shaped at the same time. If that’s not a perfect example of dialectical movement, I don’t know what is.

4 – Social constructionism is simply a late 20th century re-branding of dialectical materialism, and anyone who applies the term “social construct” to anything that isn’t purely abstract is actively trying to de-construct that thing. Just as people who call themselves “constructionists” are all about de-construction, dialectical materialists are opposed to materialism, which is why they are drawn to ideologies that oppose greed first and foremost.

5 – Read Dinosaur Brains: dealing with all those impossible people at work by Albert J Bernstein and Syndey Craft Rozen, it’s an excellent book on practical psychology.